Since being rescued 20 months ago from the dogfighting ring financed by Michael Vick, all but a few of the abused pit bulls have been recovering in sanctuary, foster care and adoptive homes. Now even the most traumatized of them can have a happy new year.

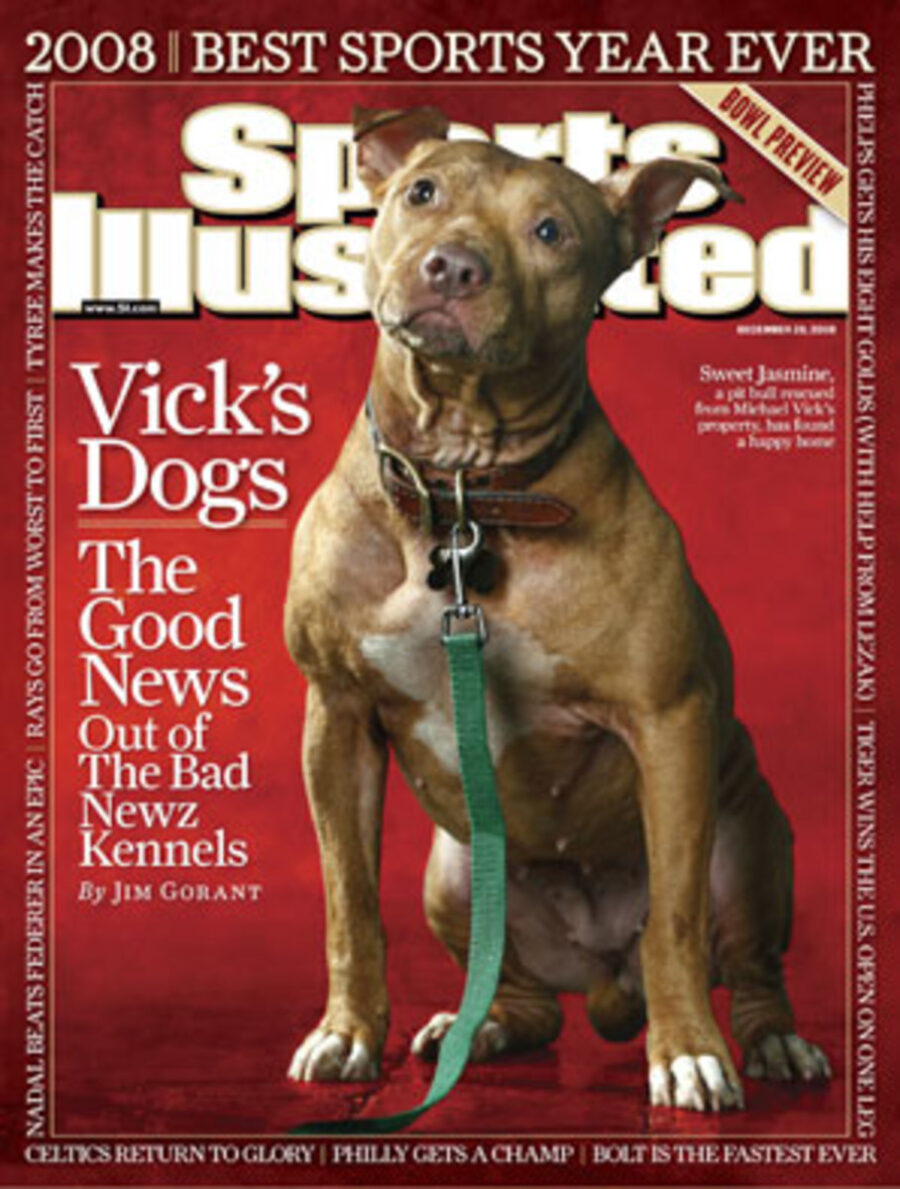

The dog approaches the outstretched hand. Her name is Sweet Jasmine, and she is 35 pounds of twitchy curiosity with a coat the color of fried chicken, a pink nose and brown eyes. She had spent a full 20 seconds studying this five-fingered offering before advancing. Now, as she moves forward, her tail points straight down, her butt is hunched toward the ground, her head is bowed, her ears pinned back. She stands at maybe three quarters of her height.

She gets within a foot of the hand and stops. She licks her snout, a sign of nervousness, and looks up at the stranger, seeking assurance. She looks back to the hand, licks her snout again and begins to extend her neck. Her nose is six inches away from the hand, one inch, half an inch. She sniffs once. She sniffs again. At this point almost any other dog in the world would offer up a gentle lick, a sweet hello, an invitation to be scratched or petted. She’s come so far. She’s so close.

But Jasmine pulls away.

PETA wanted Jasmine dead. Not just Jasmine, and not just PETA. The Humane Society of the U.S., agreeing with PETA, took the position that Michael Vick’s pit bulls, like all dogs saved from fight rings, were beyond rehabilitation and that trying to save them was a misappropriation of time and money. “The cruelty they’ve suffered is such that they can’t lead what anyone who loves dogs would consider a normal life,” says PETA spokesman Dan Shannon. “We feel it’s better that they have their suffering ended once and for all.” If you’re a dog and People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals suggests you be put down, you’ve got problems. Jasmine has problems.

They began in 2001, about the same time Vick started cashing NFL paychecks and bought a 15-acre plot of land at 1915 Moonlight Road in Smithville, Va. The property sits across from a Baptist church. A bright green lawn surrounds a white brick house that has a pool and a basketball court in the backyard and is bordered by a white picket fence. When Vick bought the land, the house didn’t exist and wouldn’t be built for a few years. It wasn’t a priority. The Atlanta Falcons’ new quarterback never intended to live there.

Beyond the house, shrouded by trees, were five sheds painted black from top to bottom, including the windows and doors. Past them were scattered wire cages and wood doghouses. Farther still, where the trees got thicker, two partly buried car axles protruded from the ground. This was the home of Bad Newz Kennels, the dogfighting operation that Vick and three of his buddies started a year after Vick became the first pick of the 2001 NFL draft. When local and state authorities busted the operation in April 2007, 51 pit bulls were seized, Jasmine among them.

By most estimates Jasmine is around four years old, which means she was most likely born into Bad Newz, and her life there fit the kennel’s name. A few of the dogs, probably pets, were kept in one of the sheds. The fighters and a handful of dogs that Bad Newz housed for other people lived in the outdoor kennels. The rest – dogs that were too young to fight, were used for breeding or were kept as bait dogs for the fighters to practice on – were chained to the car axles in the woods.

The water in the bowls was speckled with algae. Females were strapped into a “rape stand” so the dogs could breed without injuring each other. Some of the sheds held syringes and other medical supplies, and training equipment such as treadmills and spring bars (from which dogs hung, teeth clamped on rubber rings, to strengthen their jaws). The biggest shed had a fighting pit, once covered by a bloodstained carpet that was found in the woods.

According to court documents, from time to time Vick and his cohorts “rolled” the dogs: put them in the pit for short battles to see which ones had the right stuff. Those that fought got affection, food, vitamins and training sessions. The ones that showed no taste for blood were killed – by gunshot, electrocution, drowning, hanging or, in at least one case, being repeatedly slammed against the ground.

It’s impossible to say what Jasmine saw while circling the axles deep in the woods, but dogs can hear a tick yawn at 50 yards. The sounds of the fights and the executions undoubtedly filtered through the trees.

“Multiple studies have shown that if you take two mammals, say rats, and put them in boxes side by side, then give the first one electric shocks, the reaction of the second one – in terms of brain-wave and nervous-system activity – will be identical,” says Stephen Zawistowski, a certified applied animal behaviorist and an executive vice president of the ASPCA. “The trauma isn’t limited to the animal that’s experiencing the pain.”

In a sense, then, whatever atrocities any of the dogs suffered at 1915 Moonlight Road, all of them suffered. So one would think that April 25, 2007, the day law-enforcement officials took the dogs from the Vick compound, would have been a good one for Jasmine.

Zippy is not a big dog, but she’s a pit bull, one of the Vick pit bulls, and she’s up on her hind legs straining against the collar, her front paws paddling the air like a child’s arms in a swimming pool. The woman holding her back, Berenice Mora-Hernandez, is not big either, and as she digs in her heels, it’s not clear who will win the tug-of-war. “Watch it!” she says to the visitors who stand frozen in her doorway. “Be careful. Sometimes she pees when she gets excited, and I don’t want her to get you.” And just like that Zippy whizzes on the floor. Twice.

Berenice’s six-year-old daughter, Vanessa, disappears and returns with a few paper towels. The spill absorbed, Zippy is set free to jump up and lick and wag her hellos before she leads everyone into the family room, where Berenice’s husband, Jesse, sits with the couple’s five-week-old son, Francisco, and two other dogs, who rise in their pens and start barking. But Zippy has no interest in them. Instead she leaps onto the couch where Vanessa’s nine-year-old sister, Eliana, is waiting. Vanessa joins them, and over the next 15 minutes the two girls do everything possible to provoke an abused and neglected pit bull who’s been rescued from a dogfighting ring. They grab Zippy’s face, yank her tail, roll on top of her, roll under her, pick her up, swing her around, stick their hands in her mouth. Eliana and Zippy end up nose to nose. The girl kisses the dog. The dog licks the girl’s entire face.

Zippy is proof that pit bulls have an image problem. In truth these dogs are among the most people-friendly on the planet. It has to be. In an organized dogfight three or four people are in the ring, and the dogs are often pulled apart to rest before resuming combat. (The fight usually ends when one of the dogs refuses to reengage.) When separating two angry, adrenaline-filled animals, the handlers have to be sure the dogs won’t turn on them, so over the years dogfighters have either killed or not bred dogs that showed signs of aggression toward humans. “Of all dogs,” says Dr. Frank McMillan, the director of well-being studies at Best Friends Animal Society, a 33,000-acre sanctuary in southern Utah, “pit bulls possess the single greatest ability to bond with people.”

Perhaps that’s why for decades pit bulls were considered great family dogs and in England were known as “nanny dogs” for their care of children. Petey in The Little Rascals was a pit bull, as was Stubby, a World War I hero for his actions with the 102nd Infantry in Europe, such as locating wounded U.S. soldiers and a German spy. Most dog experts will attest that a pit bull properly trained and socialized from a young age is a great pet.

Still, pit bulls historically have been bred for aggression against other dogs, and if they’re put in uncontrolled situations, some of them will fight, and if they’re not properly socialized or have been abused, they can become aggressive toward people. It doesn’t mean that all pit bulls are instinctively inclined to fight, but there is that potential. Bad Newz killed dogs because it couldn’t get them to be aggressive enough. The kennel also raised at least two grand champions, dogs with a minimum of five wins apiece.

“A pit bull is like a Porsche. It’s a finely tuned, highly muscled athlete,” says Zawistowski. “And just like you wouldn’t give a Porsche to a 16-year-old, you don’t want just anyone to own a pit bull. It should be someone who has experience with dogs and is willing to spend the time, because with training and proper socialization you will get the most out of them as pets.”

The pit bull’s p.r. mess can be likened to a lot of teens driving Porsches – accidents waiting to happen. Too many dogs were irresponsibly bred, encouraged to be aggressive or put in situations in which they could not restrain themselves, and pit-bull maulings became the equivalent of land-based shark attacks, guaranteeing a flush of screaming headlines and urban mythology. Some contend that this hysteria reached its apex with a 1987 Sports Illustrated cover that featured a snarling pit bull below the headline beware of this dog. Despite the more balanced article inside, which was occasioned by a series of attacks by pit bulls, the cover cemented the dogs’ badass cred, and as rappers affected the gangster ethos, pit bulls became cool. Suddenly, any thug or wannabe thug knew what kind of dog to own. Many of these people didn’t know how to train or socialize or control the dogs, and the cycle fed itself.

Three pit bulls attacked 10-year-old Shawn Jones near the Hernandezes’ town in Northern California 7 1/2 years ago, tearing off the boy’s ears and causing other injuries, but Berenice stood up for the breed then and still does. “It’s almost always the owner, not the dog,” she says, who’s responsible for aggressive behavior. Her family has been “fostering” pit bulls – minding them in their house in Concord until they can be adopted – for nine years and has never had a problem with one. “These girls have grown up with pit bulls their whole lives, and they’ve loved every one of them.”

That wasn’t hard to do with Zippy. When she arrived from the rescue group BAD RAP (Bay Area Doglovers Responsible About Pitbulls) in October 2007, “she was afraid of her own shadow,” says Berenice. Loud noises made her jump, and when she entered another room she’d crawl through the doorway on her belly. That lasted about six weeks, but once Zippy got comfortable she took over the house. She races from room to room, goes for runs with Berenice and plays in the yard with the other two dogs: the family’s big blue pit bull, Crash, and another foster dog, Roller, a bulldog-pit mix.

As the girls run out of energy, Zippy moves on. She pops up from below the tangle of limbs and black hair that are Eliana and Vanessa and prances over to Jesse, who’s still holding his infant son. Zippy noses up to the baby, takes a few sniffs and then licks his foot. Taste test concluded, she shoots over to the side door, pushes down the handle with her snout and disappears into the side yard. “You see that?” Berenice says. “This one’s so smart. I never had another dog here who figured out how to do that.” Moments later there’s a little rap at the door. Berenice pulls it open and in comes Zippy, ears up, tail wagging.

Eliana, meanwhile, has pulled a spiral-bound notebook from her book bag. It’s late November, and she wants to read a Thanksgiving essay she wrote at school. As her little voice takes hold of the room, Zippy curls into a circle beside her. The last lines of the story go like this: “Zippy is one of a kind. I named her Zippy because she is really fast. I don’t want any of my dogs to be adopted.”

After being taken from the Moonlight Road property, Vick’s dogs were dispersed to six animal-control facilities in Virginia. Conditions differed slightly from place to place, but for the most part each dog was kept alone in a cage for months at a time. They were often forced to relieve themselves where they stood, and they weren’t let out even while their cages were being cleaned; attendants simply hosed down the floors with the dogs inside. They were given so little attention because workers assumed they were dangerous and would be put down after Vick’s trial. The common belief is that any money and time spent caring for dogs saved from fight rings would be better devoted to the millions of dogs already sitting in shelters, about half of which are destroyed each year.

What the pit bulls had going for them was the same thing that had once seemed to doom them: Michael Vick. They were, in a sense, celebrities, and there was a massive public outcry to help them. Letters and e-mails poured in to the offices of Judge Henry E. Hudson and of Mike Gill, assistant U.S. attorney for the Eastern District of Virginia. In the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, Gill had worked on several animal-related cases and still had ties to the rescue community. He reached out to, among others, Zawistowski. Could the ASPCA put together a team to evaluate the animals and determine if any of them could be saved?

Around the same time Donna Reynolds, the executive director and cofounder, along with her husband, Tim Racer, of BAD RAP, sent Gill a seven-page proposal suggesting a dog-by-dog evaluation to see if any could be spared. The couple, who have placed more than 400 pit bulls in new homes during the last 10 years, knew it was a long shot. It’s faster and easier to judge the entire barrel as rotten. Zawistowski put together a team composed of himself, two other ASPCA staffers, three outside certified animal behaviorists and three members of BAD RAP, including Reynolds and Racer.

On Aug. 23, 2007, Vick appeared in U.S. District Court in Richmond, and Judge Hudson accepted a plea agreement in which the former quarterback admitted that he had been involved in dogfighting and had personally participated in killing animals. The agreement required him to pay $928,000 for the care and treatment of the dogs, including any humane destruction deemed necessary. “That was the landmark moment – when he not only gave the dogs the money but referred to it as restitution,” says Zawistowski. “That’s when these dogs went from weapons to victims.”

On Sept. 4, 5 and 6, under tight security and a court-imposed gag order, Zawistowski’s team assembled in Virginia. It quickly agreed on a protocol for testing the dogs that would show their level of socialization and aggressiveness. Among other things, the dogs were presented with people, toys, food and other dogs. Their reactions and their overall demeanor were evaluated. In those three days the team assessed 49 dogs at six sites.

It didn’t help that the assessors had no idea what to expect. Besides their time at Bad Newz, the dogs had spent four months locked up in shelters with minimal attention. That alone could push many dogs over the brink. “I thought, If we can save three or four, it will be fantastic,” Reynolds says.

Adds Racer, “We had been told these were the most vicious dogs in America.”

So what they found in the pens caught them off guard. “Some of them were just big goofy dogs you’d find in any shelter,” says Zawistowski. No more than a dozen were seasoned fighters, and few showed a desire to harm anything.

“We were surprised at how little aggression there was,” says Reynolds. Many of the dogs had all but shut down. They cowered in the corners of their kennels or stood hunched with their heads lowered, their tails between their legs and their feet shifting nervously. Some didn’t want to come out. As far as they knew bad things happened when people came. Bad things happened when they were led out of their cages.

One dog was so scared that even the confines of her kennel offered her no comfort. Shelter workers used a blanket to construct a little tent inside her cage that she could duck under. Remembering that dog, McMillan says, “Jasmine broke my heart.”

Jonny Justice likes to lie in a splash of sunlight that stretches across the floor of the living room in the San Francisco split-level of Cris Cohen. Head lolling back, eyes closed, legs sticking up in the air, he lets the rays warm his pink belly. Comfy as this is, Jonny doesn’t have long to linger. He’s on a tight schedule. He’s up every day at 6 a.m., out for a 45-minute walk, making sure to avoid the garbage trucks, which freak him out. After that it’s back home for a handful of food, some grooming, a quick scratch-down and then into his dog bed with a few toys and food puzzles. At lunchtime he’s back out for a quick trip to the yard, some play time and a little lounging in the sun, followed by a return to the kennel until around 4:30. Then it’s another long walk – an hour this time – dinner, a game of fetch in the yard, quiet time and sleep.

After the ASPCA-led evaluations, the dogs were put into one of four categories: euthanize; sanctuary 2 (needs lifetime care given by trained professionals, with little chance for adoption); sanctuary 1 (needs a controlled environment, with a greater possibility of adoption); and foster (must live with experienced dog owners for a minimum of six months, and after further evaluation adoption is likely). Rebecca Huss, a professor at the Valparaiso (Ind.) University School of Law and an animal-law expert, was placed in charge of the dispersal.

Jonny was a foster dog that was taken in by Cohen, a longtime BAD RAP volunteer who owns another pit bull, Lily, and had cared for seven previous fosters. “When he first came, I could see he was dealing with some serious stress,” Cohen says of Jonny. “Everything scared him: running water, flushing toilets, rattling pots. He was like Scooby-Doo seeing a ghost – he’d jump straight in the air and take off. We dealt with that by putting him on a solid routine. Everything the same, every day. Dogs thrive on that. If they know what to expect, they can relax.”

“You ease their fears by building confidence through simple everyday tasks,” says McMillan. “We have to show them that the world is not out to harm them. It’s a peaceful, trustworthy place.”

After about two months, Jonny began to chill out, and Cohen started working on his manners. “His original name was Jonny Rotten,” Cohen says, “because he was such a little monster. He’d never lived in a house before. He didn’t know his name. He had no clue what stairs were or how to go up them. He’d tie you up in the leash every time you took him out. He’d just flat out run into stuff.” Jonny responded to weekly obedience training and to Cohen’s personal training, and in a few months his name was changed from Rotten to Justice.

During a walk in Golden Gate Park one day, Jonny was mobbed by a group of kids. Cohen wasn’t sure how Jonny would react to all those little hands thrust at him, but the dog loved it. He played with the children, and Cohen realized Jonny had an affinity for them. He enrolled Jonny in training for the program Paws for Tales, in which kids who get nervous reading aloud in class practice their skills by reading to a canine audience of one. Jonny was certified in November, and now once a month he sits patiently listening to children read.

He’s not the only one of Vick’s former dogs lending a hand. Leo, who lives with foster mother Marthina McClay in Los Gatos, Calif., is a certified therapy dog who spends two to three hours a week visiting cancer patients and troubled teens. Two other dogs are also therapy dogs, and two more are in training. A total of six have earned Canine Good Citizen certificates, issued by the American Kennel Club to dogs who pass a series of 10 tests, including walking through a crowd and reacting to unexpected sights and sounds. “It’s great to show people how much these dogs have to offer,” says Cohen.

Jasmine runs in the yard of the small suburban Baltimore house, jumping on Sweet Pea, another pit bull, and nipping at the back of her neck. Sweet Pea spins and leaps into Jasmine, and the two tumble together for a minute, then pop up and continue their romp. When they roll around it’s difficult to tell one from the other, because they are the exact same color. Sweet Pea is a few years older and a little bigger, and she has markings that Jasmine does not: a series of scars on her snout and head indicative of combat. Still, Sweet Pea loves to be around other dogs. She and Jasmine have a special connection and have brought each other a bit of peace. The people who know them best think that Sweet Pea is probably Jasmine’s mother. That’s why their families try to arrange play dates for them twice a month.

Jasmine wound up in the hands of Catalina Stirling, a 35-year-old artist who lives with her husband, Davor Mrkoci, 32, an electrical engineer; her children, Nino (4 1/2) and Anais (2 1/2); Rogue, a spunky spaniel-lab mix; Desmond, a three-legged foster basenji-lab mix; and Thaiz, the family cat. The fenced yard is big enough for running, and the living-dining area, which contains almost no furniture, has a smattering of dog beds and water bowls. Catalina and her children have painted angels on one wall.

In her evaluation Jasmine was considered for sanctuary with Best Friends, but when volunteers from the Baltimore rescue group Recycled Love went to see the pit bulls at the Washington (D.C.) Animal Rescue League, a volunteer was so moved by the sight of Jasmine hiding under the blanket that she crawled into the cage and began massaging and whispering to the dog. Jasmine seemed to respond. So Huss sent Jasmine and Sweet Pea to Recycled Love, which subsequently turned Jasmine over to the woman who had crawled into the cage: Catalina Stirling.

Despite a promising start, Jasmine had a long way to go. For months she sat in her little cage in Stirling’s house and refused to come out. “I had to pick her up and carry her outside so she could go to the bathroom,” Stirling says. “She wouldn’t even stand up until I had walked away. There’s a little hole in the yard, and once she was done, she would go lie in the hole.” It was three or four months before Jasmine would exit the cage on her own, and then only to go out, relieve herself and lie in the hole. Sweet Pea, who’s better adjusted but still battles her own demons, was an hour away, and her visits helped draw out Jasmine. After six months Stirling could finally take both dogs for a walk in a big park near her house.

Jasmine has come far, but she still has many fears. Around people she almost always walks with her head and tail down. She won’t let anyone approach her from behind, and she spends most of the day in her pen, sitting quietly, the open door yawning before her. Stirling works with her endlessly. “I feel like what I do for her is so little compared with what she does for me,” she says, welling up.

In the end, 47 of the 51 Vick dogs were saved. (Two died while in the shelters; one was destroyed because it was too violent; and another was euthanized for medical reasons.) Twenty-two dogs went to Best Friends, where McMillan and his staff chart their emotional state daily; almost all show steady improvement in categories such as calmness, sociability and happiness. McMillan believes 17 of the dogs will eventually be adopted, and applicants are being screened for the first of those. The other 25 have been spread around the country; the biggest group, 10, went to California with BAD RAP. Fourteen of the 25 have been placed in permanent homes, and the rest are in foster care.

Still, it’s Jasmine, lying in her kennel, who embodies the question at the heart of the Vick dogs’ story. Was it worth the time and effort to save these 47 dogs when millions languish in shelters? Charmers such as Zippy and Leo and Jonny Justice seem to provide the obvious answer, but even for these dogs any incidence of aggression, provoked or not, will play only one way in the headlines. It’s a lifelong sentence to a very short leash. PETA’s position is unchanged. “Some [of the dogs] will end up with something resembling a normal life,” Shannon says, “but the chances are very slim, and it’s not a good risk to take.”

Then there are dogs like Lucas, who will never leave sanctuary because of his history as a fighter, and Jasmine and Sweet Pea, who will never leave their Recycled Love families. “There was a lot of discussion about whether to save all of the sanctuary cases,” says Reynolds, “but in the end [Best Friends] decided that’s what they are there for. There are no regrets.”

BAD RAP works out of Oakland Animal Services, where above the main entrance is inscribed a Gandhi quote that dog people cite often: the greatness of a nation and its moral progress can be judged by the way its animals are treated.

“Vick showed the worst of us, our bloodlust, but this rescue showed the best,” Reynolds says. “I don’t think any of us thought it was possible to save these dogs – the government, the rescuers, the regular people – but we surprised ourselves.”

Jasmine doesn’t know about any of that as she sits on the back deck of Stirling’s house. Stirling kneels next to her, gently stroking the dog’s back. “I used to think any dog could be rehabbed if you gave it food, exercise and love,” she says, “but I know now it’s not totally true. Jasmine’s happy, but she’ll never be like other dogs.”

It’s quiet for a moment, and the breeze blows a shower of brown and red leaves off the trees. Then Jasmine turns, looks up, and licks Catalina’s face. It is the sweetest of kisses.

To support animal-care groups cited in this article, go to their respective Web sites: www.aspca.org, www.badrap.org, www.bestfriends.org,www.recycledlove.organd http://www.ourpack.org/.